Post by zodiac on Nov 29, 2021 16:59:53 GMT

Babylonian astrology is the earliest recorded organized system of astrology, arising in the 2nd millennium BC. There is speculation that astrology of some form appeared in the Sumerian period in the 3rd Millennium BC, but the isolated references to ancient celestial omens dated to this period are not considered sufficient evidence to demonstrate an integrated theory of astrology. The history of scholarly celestial divination is therefore generally reported to begin with late Old Babylonian texts (c. 1800 BC), continuing through the Middle Babylonian and Middle Assyrian periods (c. 1200 BC).

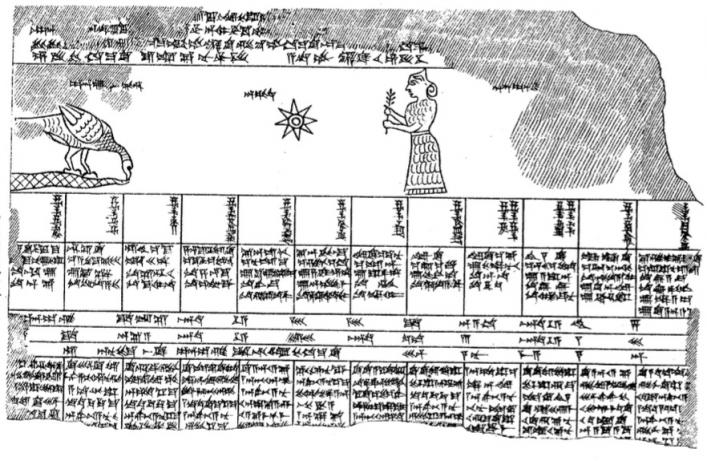

By the 16th Century BC, the extensive employment of omen-based astrology can be evidenced in the compilation of a comprehensive reference work known as Enuma Anu Enlil. Its contents consisted of 70 cuneiform tablets comprising 7,000 celestial omens. Texts from this time also refer to an oral tradition - the origin and content of which can only be speculated upon. At this time, Babylonian astrology was solely mundane - concerned with the prediction of weather and political matters - and prior to the 7th Century BC, the practitioners' understanding of astronomy was fairly rudimentary. Astrological symbols likely represented seasonal tasks and were used as a yearly almanac of listed activities to remind a community to do things appropriate to the season or weather (such as symbols representing times for harvesting, gathering shell-fish, fishing by net or line, sowing crops, collecting or managing water reserves, hunting and seasonal tasks critical in ensuring the survival of children and young animals for the larger group). By the 4th Century, their mathematical methods had progressed enough to calculate future planetary positions with reasonable accuracy, at which point extensive ephemerides began to appear.

Babylonian astrology developed within the context of divination. A collection of 32 tablets with inscribed liver models, dating from about 1875 BC, are the oldest known detailed texts of Babylonian divination and these demonstrate the same interpretational format as that employed in celestial omen analysis. Blemishes and marks found on the liver of the sacrificial animal were interpreted as symbolic signs that presented messages from the gods to the king.

The gods were also believed to present themselves in the celestial images of the planets or stars with whom they were associated. Evil celestial omens attached to any particular planet were therefore seen as indications of dissatisfaction or disturbance of the god that planet represented. Such indications were met with attempts to appease the god and find manageable ways by which the god's expression could be realised without significant harm to the king and his nation. An astronomical report to the king Esarhaddon concerning a lunar eclipse of January 673 BC shows how the ritualistic use of substitute kings or substitute events combined an unquestioning belief in magic and omens with a purely mechanical view that the astrological event must have some kind of correlate within the natural world:

... In the beginning of the year a flood will come and break the dikes. When the Moon has made the eclipse, the king, my lord, should write to me. As a substitute for the king, I will cut through a dike, here in Babylonia, in the middle of the night. No one will know about it.

Ulla Koch-Westenholz, in her 1995 book Mesopotamian Astrology, argues that this ambivalence between a theistic and mechanic worldview defines the Babylonian concept of celestial divination as one which, despite its heavy reliance on magic, remains free of implications of targeted punishment with the purpose of revenge, and so “shares some of the defining traits of modern science - it is objective and value-free, it operates according to known rules; and its data are considered universally valid and can be looked up in written tabulations". Koch-Westenholz also establishes the most important distinction between ancient Babylonian astrology and other divinatory disciplines as being that the former was originally exclusively concerned with mundane astrology, being geographically oriented and specifically applied to countries cities and nations; and almost wholly concerned with the welfare of the state and the king as the governing head of the nation. Mundane astrology is therefore known to be one of the oldest branches of astrology. It was only with the gradual emergence of horoscopic astrology from the 6th Century BC that astrology developed the techniques and practice of natal astrology.

[Wikipedia]

By the 16th Century BC, the extensive employment of omen-based astrology can be evidenced in the compilation of a comprehensive reference work known as Enuma Anu Enlil. Its contents consisted of 70 cuneiform tablets comprising 7,000 celestial omens. Texts from this time also refer to an oral tradition - the origin and content of which can only be speculated upon. At this time, Babylonian astrology was solely mundane - concerned with the prediction of weather and political matters - and prior to the 7th Century BC, the practitioners' understanding of astronomy was fairly rudimentary. Astrological symbols likely represented seasonal tasks and were used as a yearly almanac of listed activities to remind a community to do things appropriate to the season or weather (such as symbols representing times for harvesting, gathering shell-fish, fishing by net or line, sowing crops, collecting or managing water reserves, hunting and seasonal tasks critical in ensuring the survival of children and young animals for the larger group). By the 4th Century, their mathematical methods had progressed enough to calculate future planetary positions with reasonable accuracy, at which point extensive ephemerides began to appear.

Babylonian astrology developed within the context of divination. A collection of 32 tablets with inscribed liver models, dating from about 1875 BC, are the oldest known detailed texts of Babylonian divination and these demonstrate the same interpretational format as that employed in celestial omen analysis. Blemishes and marks found on the liver of the sacrificial animal were interpreted as symbolic signs that presented messages from the gods to the king.

The gods were also believed to present themselves in the celestial images of the planets or stars with whom they were associated. Evil celestial omens attached to any particular planet were therefore seen as indications of dissatisfaction or disturbance of the god that planet represented. Such indications were met with attempts to appease the god and find manageable ways by which the god's expression could be realised without significant harm to the king and his nation. An astronomical report to the king Esarhaddon concerning a lunar eclipse of January 673 BC shows how the ritualistic use of substitute kings or substitute events combined an unquestioning belief in magic and omens with a purely mechanical view that the astrological event must have some kind of correlate within the natural world:

... In the beginning of the year a flood will come and break the dikes. When the Moon has made the eclipse, the king, my lord, should write to me. As a substitute for the king, I will cut through a dike, here in Babylonia, in the middle of the night. No one will know about it.

Ulla Koch-Westenholz, in her 1995 book Mesopotamian Astrology, argues that this ambivalence between a theistic and mechanic worldview defines the Babylonian concept of celestial divination as one which, despite its heavy reliance on magic, remains free of implications of targeted punishment with the purpose of revenge, and so “shares some of the defining traits of modern science - it is objective and value-free, it operates according to known rules; and its data are considered universally valid and can be looked up in written tabulations". Koch-Westenholz also establishes the most important distinction between ancient Babylonian astrology and other divinatory disciplines as being that the former was originally exclusively concerned with mundane astrology, being geographically oriented and specifically applied to countries cities and nations; and almost wholly concerned with the welfare of the state and the king as the governing head of the nation. Mundane astrology is therefore known to be one of the oldest branches of astrology. It was only with the gradual emergence of horoscopic astrology from the 6th Century BC that astrology developed the techniques and practice of natal astrology.

[Wikipedia]